Frank Stella

In the pantheon of post-war American artists, Frank Stella (b. 1936) remains one of the most prolific interrogators of abstraction. Initially responding to the gestures of abstract expressionism, Stella’s work has evolved from expanded and shaped geometric canvases, such as the Protractor series (1967–1971), into monumental sculpture.

In the same year as his celebrated retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (for which Frank Stella was, and is, the youngest artist afforded such an exhibition with MoMA at merely 33 years old), the architect Richard Meier gifted Stella with a copy of Wooden Synagogues (1969). The text, compiled by Maria Kazimierz Piechotka, exposed Stella to Jewish visual culture in Eastern Europe, much of which had been destroyed in World War II.

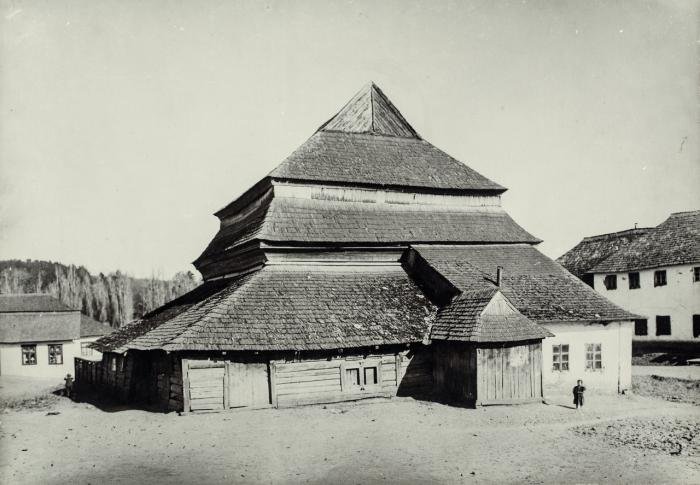

Wooden synagogue in Hvidzets’ (Gwoździec), Ukraine.

Stella’s attraction to the architectural forms of the synagogues saved by the renderings and photographs in the Piechotkas’ text dovetailed with a surging interest in returning to the origins of painterly abstraction, namely the work of Russian Suprematist Kazimir Malevich. Despite a politically charged climate during the height of the Cold War, several exhibitions and publications in the 1960s and 1970s highlighted Eastern European abstraction, especially MoMA’s 15 Polish Painters (1961) and Constructivism in Poland, 1923–1936 (1976). Inspired by the interlocking geometric forms of Wooden Synagogues and the early history of abstraction, Stella mounted a radical departure in his work through the Polish Village series (1970–1974).

Installation view of the exhibition "16 Americans" including Frank Stella's Tomlinson Court Park (left) and Arundel Castle (right) from the Black Paintings series. December 16, 1959 — February 17, 1960. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN656.29. Photograph by Rudy Burckhardt.

Unlike Stella’s earlier minimalist works invoking Nazi iconography and the Holocaust, such as those included in the Black Paintings series (1958–1960), the Polish Village series takes up lost vernacular geometric forms, turning long-standing concerns of historical memory toward its victims rather than its perpetrators. As much as this series may be understood through the notions of construction, the Polish Village series acknowledges the inherent deconstruction–or more forcefully, destruction–of its sites of inspiration. Each work, like Gabin (1972), is titled after the village in which the synagogue referent was sited, suffusing the formally ambitious orientation of the series with an elegiac and critical tone.

Frank Stella

Gabin, 1972

Acrylic and fabric collage on paperboard

34 1/4 x 30 inches

In the Polish Village series, Stella used materials such as wood, felt, press and mortar boards to depict abstract forms in high relief: a radical departure from the characteristic flatness of his earlier paintings. As if returning to the lost sites of its subject, the works in the Polish Village series were reproduced in three distinct iterations, characterized by a transition from one-dimensional collages on canvas to three-dimensional planes. Each iteration in a series retains the basic forms of the first work, as exemplified by the comparison between the sketch for Gabin (1972) (above) and Gabin I (1971) (below). For Stella, novelty is never completely new.

In a 1988 review of Stella's reliefs, which include the Polish Village series, critic Adam Gopnik lauded Stella for the ability to be "an academic and a rebel—both the best student in the class and the worst truant," which keeps his art "from ever being boring." (New Yorker, January 4, 1988)